The relationship between founders and investors is a weird, symbiotic phenomenon.

We, entrepreneurs, create companies, we work day and night, we lose sleep and get gray hair to see our vision through- and someone on the other side provides the funding, and just sits and relax while we make them money.

That’s just a rookie oversimplification. The reality is, most of the companies, most of the startups that you can think of, could not exist if it wasn’t for venture capital. That includes your Google, your Airbnb, your ClickUp, your TikTok, even your Candy Crush and your Telegram.

Garry Tan published a video the other day on how he turned a $300K investment into $2B.

Anyway, he invested in Coinbase, in their first ever round of funding, and now that Coinbase went public his investment has multiplied over 6000x.

This is transformative, life-changing money. Tan went from entrepreneur, to being worth a few million dollars, to being worth hundreds of millions, all with one accurate bet.

That is very much the investment thesis of venture capital. Most startups fail, everybody knows that. Most startups will fail. Experienced investors are very much prepared to lose their money, because they are not looking for 1x or 2x returns on investment, they are looking for that 6000x, unicorn, life-changing win.

You would think that there’s a simple approach to it. I have money, I invest, I get money if the company succeeds- but there is a whole industry of venture capital, with layers of partners, limited partners, funds and legal structures- and most entrepreneurs come into this world having no idea how any of this stuff works. Many investors too, actually.

I had a broad idea of how it worked, but as I researched this video I realized how hard this info is to find and to understand. Luckily for you, we are good at getting complex things into simpler form. Shameless plug. Let’s get on with the video.

So Gary Tan was probably a direct shareholder of Coinbase. He invested some of his own cash in a simple, early stage round (even called Friends and Family under the S1 Filing). This is the model of an angel investor.

As the company grows, you have institutional investors. Venture capitalists. They are not investing their own cash, but rather, other people’s money. A VC raises money from other people and decides where to invest it, in exchange for a commission.

And the economics of doing one or the other are drastically different- but before we dive into that, we need to understand the type of businesses that can raise this type of money, and how the cycle works.

Companies come in all shapes and sizes, but only a handful of them are venture-fundable.

You may hear talk in the startup press about this and that company raising millions of dollars, but for the most part, these are fast-growth, massively SCALABLE companies, and that’s why they can (and must) raise capital to expand.

There’s really no terminology to tell them apart, but I like to use Startups vs Small Businesses.

Yes, if we are strict about their definitions, all Startups begin as Small Businesses, but the difference I want to make here relates to their scale.

So let’s draw a line here and paint that picture.

Say a developer and a UI designer got tired of their day jobs. They’ve built a name and a portfolio for themselves and they decide to start their agency.

To me, this is the definition of this category of ‘small business’. This is, by all means, a tech company, but in order to scale they will need to hire more and more designers and developers. Their margins, the profit the company makes after covering expenses, will always be limited because they are essentially selling man-hours.

Can they reach great scale? They can build an agency with 1,000 engineers, but that is a long-shot. Examples here are the McKisneys and the EYs of the world: massive consulting companies that still sell mostly, services; but those are exceptions.

Can they raise venture capital? Unlikely. And definitely not at the idea or early revenue stage.

Those companies are usually formed by 2 or 3 partners who bring in some capital of their own to get started. One of those partners might even be an ‘executive’ co-founder: while the other, or others bring the expertise and the work, the executive co-founder brings the capital.

But that is not a venture capital investor. It’s probably a relationship that you’ve already built, and that trust you to get in bed with you for this business.

There’s nothing wrong with being a ‘small business’ type of company. The US economy was built on these small businesses. The majority of companies fall within this category. Just know that if this is you, venture capital is not for you.

On the other hand, we have the tech Startup. The Silicon Valley type startup.

This is the company that you read about on Techcrunch. A company that has found a transformative market opportunity, and that is using technology to solve it in an extremely scalable way.

Uber is not a car or a taxi company. It doesn’t need to hire drivers. It operates all over the world and can open an operation in a city with 3 employees, because they are a marketplace. They are connecting drivers to riders.

Same with Airbnb. They don’t need to buy homes or rooms (like a hotel), they are just connecting the players in this economy.

That’s the concept that I like to classify as a tech startup. Once again, technically, the development shop is a tech startup, but I’m not using the dictionary definition.

The story on how these companies fund their operation is very different. These are companies reaching for the moon, so they will need to raise capital every couple of years (assuming they are doing well).

For the most part, these companies will operate at a loss for years, because everyone is betting on the large play. Think Amazon, who didn’t turn a profit for decades, but today, it completely dominates the e-commerce industry. And AWS. And streaming.

Let’s look at that Coinbase round as a case study.

Coinbase went public a few months ago, and it gave us some fantastic materials. As a company goes public, they need to release their financials, which gives us everything we need to infer how much money investors made from them. We made a whole video about how that process works.

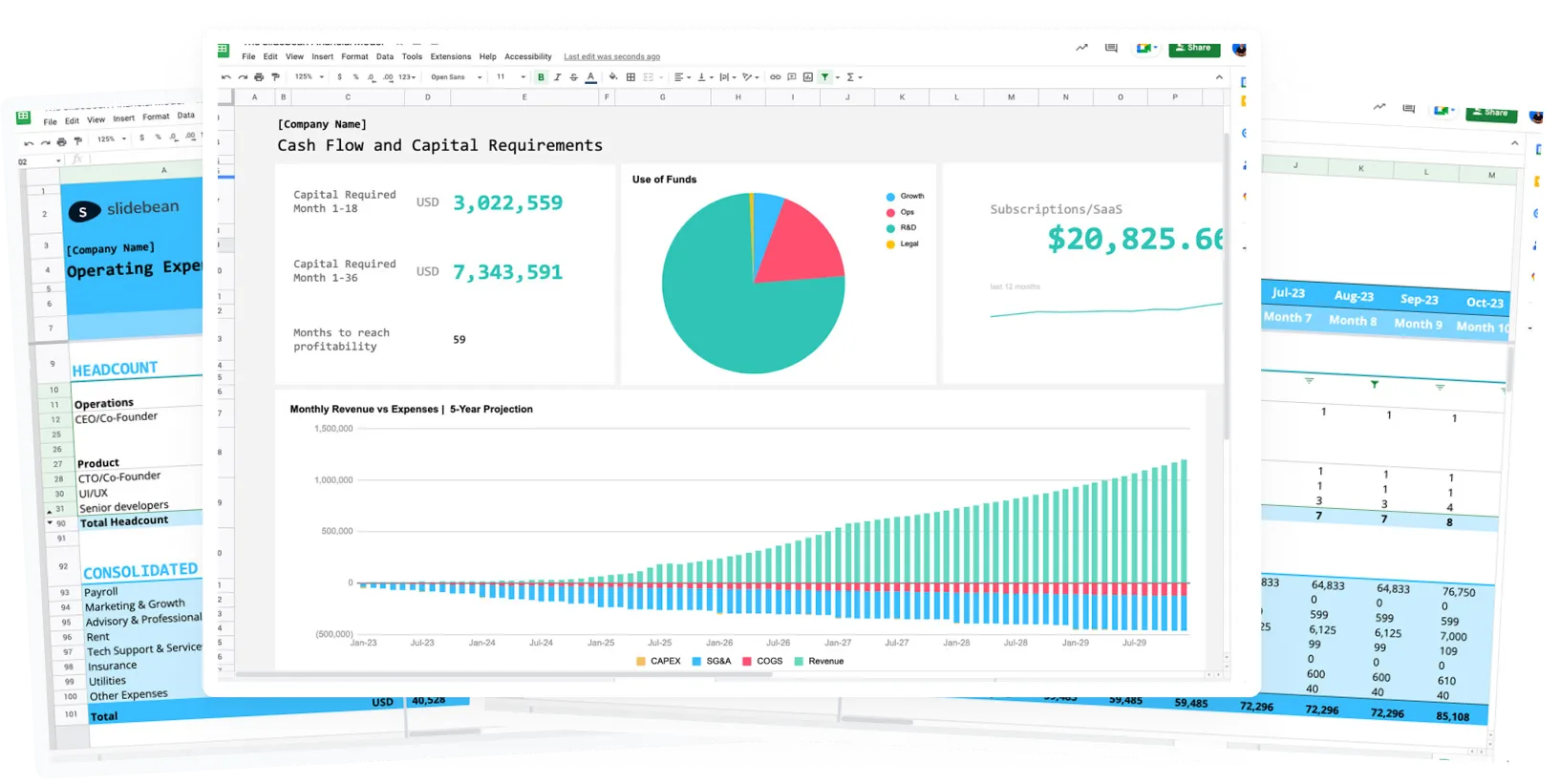

Coinbase raised, according to Crunchbase, 6 rounds of capital. From Seed/Friends and Family to Series E. The first round in September 2012, where Garry Tan participated with his $300K.

Then Series A in 2013, Series B that same year, up until a massive $300M Series E in 2018.

By the end of 2019 they were generating $533M in revenue, which doubled to $1.2B by the end of 2020. They lost money in 2019, about $30 million- but they made about $322M in profits, net profits, in 2020.

That’s a business going from $0 to $1.2B in revenue in just 8 years.That’s $322M in profit, PROFIT. Doubling revenue year on year. And there is still room to grow, which is why they went public to raise even more money.

But enough of being a groupie.

This is the funding story of Coinbase. You can see that they raised money about once a year since their inception, and here are some references on the number of users, employees and revenue they had when each one of those rounds happened.

(By the way we send a weekly Company Forensics newsletter with a similar breakdown of any company that announced funding during the week).

So let’s start at the beginning, those Angel Investors in the early stage. They are wealthy individuals investing their own capital, and the term "angel" investor. It comes not from finance but from the theater.

When a theatrical production struggled to make ends meet, it could enlist the aid of a wealthy individual that would give money to keep it alive. So, the investor believed in the production and got some interest in return if it made it big.

But the term didn't catch on in the startup world until 1978. Then, professor William Wetzel used it to describe an investor who financially supported startups. An Angel Investor can very well come in with $10K, $50K all the way up to hundreds of thousands of dollars, though investors who write checks that big are often called ‘Super Angels’. In that cycle of company funding, they usually come in the early stages. Coming into that $300M round for Coinbase with a $100K would be… out of place.

In order to be an accredited Angel Investor, according to the SEC, you have to fulfill one of two conditions: you have to have either a net worth of $1 million, excluding marriages, tax returns, and the value of your home. Or if your individual income exceeds $200,000, or the household has an income of $300,000 or more, which, in the US, is not a high bar by any means.

So the cool part is that you get to decide on what companies to invest. These are individuals, who get to meet founders, who get their hands dirty with due diligence, and with understanding the ins and outs of the business.

The most successful examples are entrepreneurs themselves, who maybe ended up with some capital after a successful startup of their own, and are now using it to invest in other founders.

The question here is experience: how do you tell the good companies from the bad ones? How do you figure out if a founder has their stuff figured out? As an Angel Investor it’s your call, and no one else’s.

So investing at these very early stages for a business is obviously more risky. Most publications agree that 75% of venture-backed startups fail. The Coinbases are true exceptions, the one in 1,000, if you will. While you can spot early traits of success, it’s really hard to tell if a company has what it takes to become a unicorn, especially at that early stage.

The additional risk for Angels is deal flow. After all they are individuals. There’s only so many startups that will be able to reach them, and there’s only so many Zoom calls they can take.

Another risk here is that as an angel, you are funding one part of the round, but not the rest. If you are the first check a company is getting, you have the additional risk of the company not being able to secure any other checks.

So overall, this is a high risk, high reward game.

So, what are the options to invest with less risk?

To overcome some of the perils of investing alone, a bridge solution was created- the concept of Angel Groups, and the concept of Syndicates.

An Angel Group is formed by an investor who is perhaps more connected, or who has a good network of wealthy individuals who want to get in on the venture capital party, but perhaps aren’t that experienced, or don’t have access to deals.

Essentially, members pay a fee to be a part of the group, and get access to the deals. Those fees are usually in the $1K to $5K/yr, and are meant to cover a small team for the Angel Group.

That may include analysts to find startups and filter them, and do some diligence, legal teams and simply the task of organizing a monthly session with investors to look at some deal options. It is A LOT of work.

BTW, some Angel Groups try to charge the entrepreneur for pitching. If you see that, run the other way.

Angel Groups also sometimes take an additional fee called a carried interest or carry. It’s a finder’s fee for the management team of the angel group. A 20% carry is pretty standard, and here’s how it works.

Let’s say one in the group chooses to invest in Slidebean, a $50K check.

Slidebean grows, kills the competition and gets acquired by SpaceX, for some reason. That investor’s stake is now worth $5M, 100x (oversimplifying to exclude some terms)

So the investor’s earnings are $5,000,000-$50,000, or $4,950,000. Out of those earnings, the 20% carry would represent $990K. So the Angel Group gets to keep that as the finder’s fee.

Now, the advantage here is you are co-investing with people. For good or worse, there is some group/herd mentality in these cases. Peer pressure might get some investors over the edge to commit to a company, but at the same time, a turned off investor can make the deal fall apart.

Another advantage for the founder is that usually, ideally, investors bring money through an investment vehicle.

Essentially, all the investors form an LLC, with proportional ownership to each of their investments. The LLC invests in the business so you end up with only one investor in the cap table.

Sounds like a small advantage, but when you have to get papers signed, it’s easier to chase the legal representative of the LLC than going to fetch the 20+ signatures. It also makes processing the carried interest a lot easier.

This legal structure only has a small annual operational cost which is shared by all investors. The deal and the potential for them is pretty similar to the Angel approach: they choose the companies, they win or lose depending on the companies they chose to invest in- except for the fees.

By the way, syndicates are rather similar, but they have been designed to be more online.

In an Angel Group there’s this idea of physicality, at least pre-covid, investors get together and they decide. It’s expected that investments will be at least $10K-$20K per investor.

On a syndicate the transaction is mostly online, and as an angel, you can come into the group with as little as $1K.

Now are those Slidebean and Coinbase successes enough to make up for the failures? Sort of, but let me get to that in a sec.

Before we dive into that, we need to understand Venture Capital funds.

The most established investment process for startups is Venture Capital.

Instead of individuals investing, a venture capital fund is formed around a person, usually called the Managing Director or the General Partner- usually called GP.

This is usually a well-known investor who has had success on a different VC fund or as an entrepreneur, and who other investors trust with their money.

You see, venture capitalists raise money themselves, to then invest it in companies. This is called a FUND. They go out to angels, institutions and raise anywhere from a few million dollars, to $100B, literally- Softbank. Go watch our video about them.

So the way this works is the General Partner goes on a roadshow to try to get investors onboard the fund. What he or she is selling is their ability to pick fantastic companies, and to help them succeed.

All this money gets put into a bucket, called a fund. It’s usually an LLC.

So the fund is a pile of cash out of which the firm invests. If it does well, a new fund gets created for a new bucket of investors. These investors are called Limited Partners, or LPs.

You’ll often see terms like Sequoia Capital fund III, or 500 Startups LLC Fund II. That’s the number of the fund that you are a part of. It’s this fund that’s an investor in the different businesses. By owning a % of that fund, you indirectly participate in all the companies the firm invested in.

The other day I was on a call with some random person, and he told me, hey, I’m your investor. After seeing my very confused face, he told me he was part of the 500 Startups fund that invested in us. It was awkward.

Some funds have a well-earned reputation for doing really well, or at least appearing to do so. Peter Thiel’s Founder’s Fund, or Sequoia Capital, Andreesen Horowitz, First Round Capital, or Union Square Ventures.

Yes, if you look at their portfolios you can see that they funded these rockstar companies before they were rockstars. Their money, their help and even the credibility of having them onboard inevitably helped catapult them.

But those are rockstar VCs, and they are the exception.

Let’s go back to Coinbase. USV invested in their $6M series A. Andreesen on their $25M Series B. Assuming those rounds translated into 10-15% of the company, they would still translate into a lot of money for everyone.

But for the Limited Partners it’s not as much as you would think, because the fees for putting your money on a VC fund are pretty high.

VCs make money in two ways. First, they collect 2% of the fund on an annual basis, for at least 4-5 years. This is essentially an asset management fee.

So on a $100M fund, for example, the annual fee would be $2M. And then another, and then another for the next few years. That’s just a cash payment regardless of how the investments did. This has drawn some criticism because it’s a hefty cash compensation that happens regardless of how the fund does.

In addition, they also make a standard 20% carried interest, the same ‘carry’ we talked about before. It gets split between team something like this:

Now if you want to geek with me about the legal structure, you have the VC firm, which is a traditional Corporation with its employees, and such.

The LPs and the fund itself invest money in the Fund, which is a separate legal entity. Again, 2% of the fund gets paid to the Firm every year. The fund invests in the startups themselves.

When the fund gets money from an acquisition or a sale, it pays 20% of the profits to the Firm, that’s the carry, and then it pays out to the Limited Partners.

This way, a Firm can have multiple funds with different groups of investors.

So does the model work? Is it profitable for investors to invest in you?

Depends.

Let’s assume an individual is faced with the choice of becoming an Angel Investor, joining a Venture Capital fund, or just putting their money on a safe bet, like an ETF.

This investor has $1,000,000 of funds that they are willing to bet.

The simplest option, by all means, is an ETF for the stock market. Most publications agree it could bring a 7-10% return after adjusting for inflation. So in 8 years, their money would grow to some $1.7M.

Let’s go with the Angel Investing scenario.

- The investor choses 20 companies, and invests an average of $50,000 in each one of them.

- The average valuation for these companies is $4M pre-money, which is pretty standard. That means the average stake this investor gets in each one of those companies is 1.25%.

- Now of course, we are assuming that $50,000 is part of a larger round. That 1.25% is the percentage that this investor gets.

As we mentioned, 75% of venture-backed startups fail, so 15 out of these companies will die.

For the 5 that are left, let’s assume that they go to raise additional capital. On average, each one of them raises 3 additional rounds of funding; so Series A through Series C. For each one of those rounds, the investor gets diluted by 20%, so their ownership per company goes from 1.25% to 0.61%.

Assuming that these 5 companies operate for 8 years, the same amount of time we used for the ETF scenario, they would need to be acquired for a combined $56M for this investor to match the earnings of the ETF.

If they wanted to get a 5x return on their $1,000,000 invested, then the sum of the acquisitions of all these companies would have to be around $164M, or an average of $32M per company.

Impossible? No. But it requires 5 good bets.

Let’s look at the math if investing with a VC fund.

An investor brings the same $1,000,000 into a VC fund.

They’ll pay 2% in fees to the firm for managing their assets, for about 5 years, that means that effectively their cash going to startups is $900,000.

This fund invests in Series A stages, which are ‘safer’. We are going to assume that not 75% of the companies will fail, but only 60%.

Let’s assume that the whole fund is about $50,000,000, so this particular investor owns 2% of it.

The fund is used to invest in 15 companies, and based on that 60% success rate, only 6 will thrive.

If the combination of these 6 companies gets sold for $260M, the VCs fund would get about $100M. That’s a profit of $55M or so, which means that the carry award for the managing partner is about $11M.

Out of the $88M left, the investor gets 2%, which is break even. That means each company needs to be sold for $43M or more in order to make the same amount of money as if they had invested in an ETF.

To 5x their investment, the companies would need to be sold for about $1.4B. That’s $233M per company.

Here’s a metric to put all this in perspective: As a percentage of total investments in past decade, how many percent of companies exit above $100 million and $500 million? How about $1, or even $2 billion?

› 3 % of companies exit above $100 million

› 0.7 % exit above $500 million

› 0.2 % exit above $1 billion

› 0.06 % exit above $2 billion

So here’s the IRR, or investment return rate for some of the funds that Andreesen Horowitz raised the past decade, as of September 2018. Notice how most of the funds are yet to outperform the S&P 500, and the only one that has achieved this was 9+ years old at the time of the study.

And this is Andreesen, not some small fund.

It is generally agreed that VCs have about a decade to raise capital, make their first and follow-on investments in portfolio startups, and then oversee their assets to the best possible financial outcome.

So there you have it, now you understand where the money for your startup might or might not come from, and hopefully, why investors rejected you. You have to prove that you can be that big.